Celebrating Black History Month: Changemakers in the History of Cancer and Medicine

This Black History Month, we at the Iowa Cancer Consortium would like to take a moment to recognize several Black and African American changemakers in the history of cancer and medicine, especially here in Iowa. There are many historical and modern icons to celebrate and these are just a few. We would like to note that a countless number of Black and African American researchers, inventors, doctors, and scientists have been lost to history due to systemic racism, the amplification of white stories, and the “white washing” of history. We honor these icons whose names are unknown.

Dr. Edward A. Carter

Edward Carter was born in Virginia in 1881, the son of formerly enslaved people. He grew up in Buxton, Iowa, which was a predominately African American coal mining town in Monroe County. (Buxton is no longer in existence and has a fascinating history.)

Edward A. Carter (Photo: University of Iowa)

Edward A. Carter (Photo: University of Iowa)

At age 26, Carter was the first African American to graduate medical school at the University of Iowa (and only the second Black student to graduate with an undergraduate degree from the university). While the University of Iowa is recognized as an early adopter of integration, Black students were not allowed to live on campus until 1945.

Carter practiced in Buxton until the coal mining company shut down in 1919, at which point he and his family moved to Des Moines where he continued serving the community. Later they moved to Detroit, where he passed away in 1956 at the age of 75.

Dr. Jane Cooke Wright

Dr. Jane Cooke Wright is often called “the mother of chemotherapy.” Born in 1919, Dr. Wright began working with her father, Dr. Louis Wright, in 1949 at the Harlem Hospital Cancer Research Center in New York.

Dr. Jane Cooke Wright (Photo: Yale University)

Dr. Jane Cooke Wright (Photo: Yale University)

While chemotherapy was in its infancy, Dr. Wright experimented with a variety of chemicals to find anti-cancer properties. In 1951, she demonstrated the effectiveness of methotrexate on breast cancer – a drug that is still used, often in combination with other drugs.

Dr. Wright held many esteemed offices in her career: president of the New York Cancer Society, professor of surgery, head of the Cancer Chemotherapy Department, and associate dean at New York Medical College. She died in 2013 at the age of 93.

Nikole Hannah-Jones

In 2020, Nikole Hannah-Jones was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for her work on The New York Times Magazine’s The 1619 Project. In Episode 4 of the 1619 podcast, Hannah-Jones details the heartbreaking story of her uncle Eddie’s illness, late diagnosis, and early death at age 50 from cancer.

Nikole Hannah-Jones (Photo: The New York Times)

Nikole Hannah-Jones (Photo: The New York Times)

Eddie lived in Waterloo, Iowa – where Hannah-Jones grew up – and the episode details how lack of access to health insurance prevented an earlier diagnosis that doctors think would’ve prolonged his life. The episode goes on to talk about the deep-seated inequities and the scientific crimes against humanity that continue to affect Black people and the care they receive to this day.

A national movement that includes stories from right here in Iowa, Hannah-Jones and The 1619 Project have given voice to the data that show that Iowa has the 2nd highest incidence rate and the 3rd highest mortality rate for all cancers combined in the Black population.

Dr. Percy Harris

Born in Durant, Mississippi, in 1927, Percy Harris lost both of his loving parents by age 11. He spent two years of his childhood in a segregated tuberculosis sanitarium in Tennessee before moving to Waterloo, Iowa, to live with his aunt. In 1948, while attending the University of Northern Iowa, he met his future wife, Lileah Furgerson – the daughter of Waterloo’s first Black physician, Dr. Lee Burton Furgerson, Jr.

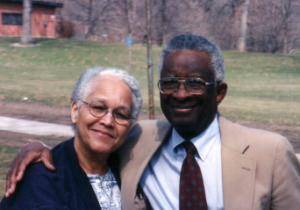

Lileah and Dr. Percy Harris (Photo: Linn County)

Lileah and Dr. Percy Harris (Photo: Linn County)

Dr. Harris graduated medical school at Howard in 1957 and accepted an internship at St. Luke’s Hospital in Cedar Rapids. While St. Luke’s provided free housing for their interns, the real estate agents charged with finding homes for the twelve incoming interns found homes for the eleven white interns, but not for Dr. Harris, his wife, and their growing family. The hospital remedied this by converting a hospital-owned home in Cedar Rapids.

In 1958, Dr. Harris opened a private practice and became the first African American physician in Cedar Rapids. He, his wife, and their twelve children, were very involved in the Cedar Rapids community in the decades to follow. Lileah passed away in 2014, and Dr. Harris died in 2017 at age 89. In 2019, the Dr. Percy and Lileah Harris Public Health Building was built in Cedar Rapids to commemorate their countless contributions.

Henrietta Lacks

The story of Henrietta Lacks’ contribution to science is a very different story than the other individuals highlighted in this post. Although Lacks’ “immortal cells” made possible the polio vaccine, the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, the COVID-19 vaccine, and countless other scientific advancements, Lacks and her family did not give consent, were not informed, and were not compensated for the use of Lacks’ cells – called HeLa cells – in scientific research. Her story is often cited along with the The U.S. Public Health Service Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee as an example of racism in healthcare, research, and public health, and a reason for ongoing distrust in African Americans towards the healthcare system.

A photograph of Henrietta Lacks (Photo: The Washington Post)

A photograph of Henrietta Lacks (Photo: The Washington Post)

Henrietta Lacks was born in Virginia in 1920. In 1951, at the age of 31, Lacks sought medical treatment at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, due to vaginal bleeding. She was diagnosed with cervical cancer and given internal radium treatments. During her treatment, a biopsy of her cancerous cells was sent to Dr. George Gey, who observed that her cells doubled every 20-24 hours instead of dying. They were “immortal,” making it possible to mass produce human cells for scientific research for the first time.

Lacks died from cervical cancer later that year, leaving behind a husband and five children. The Lacks family has sought justice over the years, and in 2013 came to an agreement with the National Institutes of Health about how the DNA can be used, and in 2023 settled out of court with a pharmaceutical company that they alleged profited from HeLa cells after their origination was known.

Dasia Taylor

What were you like in high school? While many teenagers were practicing for their driving test, studying for college entrance exams, or having fun with their friends, 17-year-old Dasia Taylor invented a revolutionary infection-detecting surgical suture in Iowa City, Iowa.

Dasia Taylor (Photo: The Des Moines Register)

Dasia Taylor (Photo: The Des Moines Register)

The sutures change color when a post-surgical infection is present – a simple concept with life saving potential. Black people are disproportionately likely to develop post-surgical infections. One reason for this disparity is that healthcare providers are trained to look for swelling and redness of the skin – symptoms that aren’t as apparent on all skin tones.

Now a college student, Taylor is working on patenting the technology and hopes there are widespread applications for her invention – especially in underserved areas that see high post-surgical infection rates.

Want to learn more?

- Connect with our Health Equity Workgroup by emailing [email protected]

- Watch how community members in Black Hawk County, Iowa, are making waves to reduce cancer health disparities in our “Stories from the Iowa Cancer Plan” video series

- See evidence-based strategies in the Iowa Cancer Plan for promoting health equity and reducing cancer health disparities in Iowa

- Read the latest Cancer in Iowa Report from the Iowa Cancer Registry to see where Iowa currently ranks for cancer incidence and mortality in the Black population